On Thiel’s 2014 Book, Zero to One: A Look into Progress (Chapters 1-3)

- Paul Kasaija

- Jan 12, 2021

- 11 min read

Updated: Feb 14, 2023

An Introduction

The famous book written by PayPal co-founder and billionaire entrepreneur Peter Thiel in 2014, Zero to One, encompasses various anecdotes and opinions from his interesting experiences as a startup founder. This is a commentary limited to the first 3 chapters, since the book has numerous topics in just the first few chapters despite being an easy read. As a disclaimer, this is not a review of Zero to One itself, but my personal take on some of the topics that Thiel introduces.

Zero to One, Chapters: Prologue & 1-2

The first issue Thiel raises in his 2014 book “Zero to One”, is a crisis from unproductivity. If a country stagnates in technology and doubles down on the old ways of doing things, it will lead to expansion of old technology, and the overextension of our world’s resources.

He continues in asking the readers a question— What important truth do few people agree with you on? Thiel delves into the subject of contrarian viewpoints in the prologue, and according to him he also asked the same question to his students in Stanford. For me, the answer was: Creativity doesn't come naturally. It also is not nurtured through practice, but from unique observation. My answer is likely different from yours or Thiel's, but he quickly gets to the point of his question: “good” contrarian viewpoints are necessary to look into the future and perceive what changes might come to how we think and believe. The future is a place where ideas that were thought to be contrary to the norm are the reality.

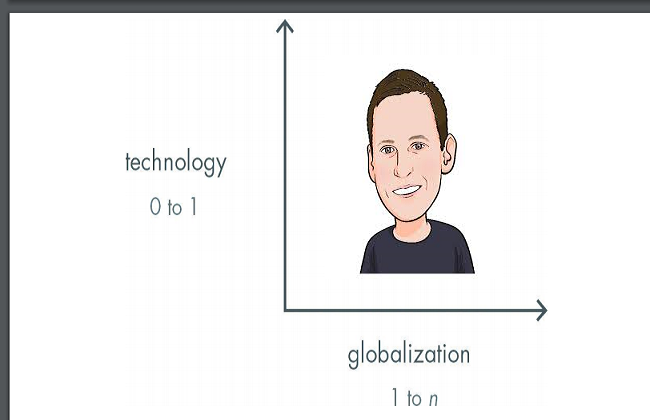

Following his question and his ideas on the future, Thiel contrasts globalization and technology. By his definition, taking things that work somewhere and making them work everywhere is "globalization", while any new and better way of doing things is "technology". In the book, Thiel shows two graphs, one with vertical/intensive progress on the y-axis and horizontal/extensive progress on the x-axis , and another with globalization on the x-axis and technology on the y-axis.

“ If you take one typewriter and build 100, you have made horizontal progress. If you have a typewriter and build a word processor, you have made vertical progress," Thiel writes. In short, vertical progress is creating new things— things that haven’t been done before.

To build his case on creating new things, he makes an example of China’s globalization, “China is the paradigmatic example of globalization; its 20-year plan is to become like the United States is today. The Chinese have been straightforwardly copying everything that has worked in the developed world”. In the next section, he further develops his point, "Without technological change, if China doubles its energy production over the next two decades, it will also double its air pollution. If every one of India’s hundreds of millions of households were to live the way Americans already do—using only today’s tools—the result would be environmentally catastrophic. Spreading old ways to create wealth around the world will result in devastation, not riches. In a world of scarce resources, globalization without new technology is unsustainable." Unlike earlier sections, this is where I diverge in opinion. His perspective on technology and globalization, to me, seems forced and overly black and white. For example, there are existing energy sources like wind and solar which can reduce pollution in developing countries without any further technological advances. Electric cars can reduce carbon emissions in countries like China and India; it's an old idea, but the benefits are clear. Now, I agree that developing countries have to be careful of environmental issues, but the effects of globalization and technology are not as simple as he states.

Here's the not-so-hidden truth about globalization: globalization of products and materials can create innovation simply by being used by someone with a different perspective than someone who uses it on this side of the world. Even technology is the result from a diverse group of ideas which are realized from a diverse group of countries producing materials that can only be found in diverse places. For an example of "good" globalization, Starlink is a program which Elon Musk created where he devised a satellite powered internet network that can create internet for developing or remote places in need. One can imagine the positive effects in terms of developing the industries, economies and technology in those countries. Those benefits return to our side of the world in the form of new markets which in turn produce mutual economic growth. In other words, globalization can lead to better technology or spontaneously create progress despite the lack of creative noise. Rather, creating new and better methods with limited uses can be way less ineffective in comparison to expanding use cases to new markets.

Moving along into Chapter 2, the economic changes of the 1990s are discussed in detail along with how many believers in the tech “bubble”, or old conventional belief”, took risks. The story of the browser technology giants that led the ‘90s is used to further expound on Thiel's point that economic progress can really only be made through new and unseen technology. In their case, the Mosaic browser’s launch in 1993 is what he points to as the catalyst for the browser market. Google, Yahoo!, Amazon, and Netscape, among other tech companies grew massively, fueling the dot-com bubble that lasted from September of 1998 to March of 2000 . The advent of consumer internet connected these companies in the pursuit of profit despite the global financial crises in Southeast Asia, Russia, and America paralyzing other markets. Throughout an entire section in Chapter 2, Thiel compares these crises of the early 90s, spurred by globalization, with the tech bubble in the '95 and the dot-com mania in 1998, in order to argue that technology is the way forward from the issues of stagnation. He further documents that after the bubble ended in March 2002, investors went into housing, leading into the housing bubble which led to the Great Recession, which furthers his point against globalization.

The major point of the first few chapters is to lay out the foundations of what leads a business to be successful and to take a broader look at startups, at people who took risks to go from "0 to 1". A quote which does a good job of summarizing his thoughts is the paragraph at the end of the second chapter, “The market high of March 2000 was obviously a peak of insanity; less obvious but more important, it was also a peak of clarity. People looked far into the future, saw how much valuable new technology we would need to get there safely, and judged themselves capable of creating it” In it, Thiel does a masterful job of summarizing his points beginning with the oxymoronic sentence capping his sentiment on the end of the dot-com bubble. Despite any discrepancies of opinion, I agree about the point of taking action and moving forward from stagnation when it comes to technology. The act of taking risks improves not only the wellbeing of the partakers but the standard of living for many people. Thiel also writes, “The most contrarian thing of all is not to oppose the crowd but to think for yourself.” One common line of thought between our perspectives, is that thinking for yourself rather than opposing the crowd is definitely the crossroads between those who say differently and those who do differently.

For me, Thiel's apt analysis of the '90s issues and triumphs reveals all the more why a combination of globalization and evolving technology is paramount to a successful business and a prosperous country.

Zero to One, Chapter 3 In Depth

What valuable company is nobody building? Valuable not just value, or in other words, what kind of company is "so good at what it does that no other firm can offer a close substitute". This is the first major question Thiel brings into the purview in the third chapter. As an expert in his field, he brings up a topic that he clearly has had experience in; meanwhile as an economics major, I can only offer a theoretical perspective here: I think that creating a new intermediary is one of the aspects that are extremely hard to innovate but have the biggest payouts of all technological improvements. Of all the types of businesses: service businesses, retailers, intermediaries, and producers, the intermediaries always have had some of the highest profits. The trend of profit shows: search engines are intermediaries, advertising companies are intermediaries, even internet and cable companies are intermediaries. However, there hasn’t been much intermediary innovation in recent decades.

One of Thiel’s minor points in chapter 3 is that Americans view competition in a rosy light, despite having a capitalist system. Yet since capitalism is the opposite of competition, it points to hypocrisy. I agree that since competition drives away profits because the market will always be driven to equilibrium by itself, it is not compatible with a pure capitalist system. What I don't agree with is that the point doesn't need to be said: it's already obvious that nations simply have too many interests to avoid hypocrisy. If the "hypocrite", America, doesn't strive for its economic ideals for competition and leverage political power to drive down the biggest fish and focus on its people, it will just fall into crony capitalism where monopolies are prioritized. Governments don’t work like businesses, and democratically elected or appointed officials rather than stocks represent its future; if a nation purely focuses on profits over people, it will fail. Eventually the building blocks of the nation, the small businesses and individual people, will have no money to put into investments or the economy and the recession will destroy businesses as well.

Summarizing the next section, Thiel writes that monopolists “lie” to make their business seem smaller, while small competitors “lie” to make their business seem grander, to lead into the point that understating the scale of competition can lead to failure. He later expounds that it is more of an exaggeration, actually: Monopolists (like Google) exaggerate the distinction of being a union of large markets rather than one, and non-monopolists (like restaurants, filmmakers) exaggerate the distinction of being an intersection of various smaller markets rather than one. This logic carries the chapter, where he pries into the distinctions and similarities between monopolies and non-monopolies. I tend to agree with this logic. Nowadays, you can see plenty of these types of exaggerations wherever you look, because some companies without any real innovation will propose something that sounds unique but proves hollow. For example, the rise of crowdfunded products on Kickstarter, Indiegogo, and GoFundMe, has led to a meteoric number of useless products crowdfunded because people are tricked by one distinct aspect. Like As Seen on TV products, they generally provide minimal innovation and just seek profit, which leads to failure in the consumer market.

Unlike the last point, the logic comprising his next few points strike me as biased and I’ll explain why. Thiel uses Google to illustrate his point that only monopolists can afford to think about things other than making money, like Google's catchphrase, "Don't be evil”. In contrast, non-monopolists are limited to the present, and can only worry about their competitors and resort to paying employees minimum wage. I actually disagree with this point. It is a false dilemma, or in other words only gives two extreme points on the spectrum of possibilities. Rather, both sides have the same issues on different scales. Polarity between pay grades for CEOs and business line executives vs. staff shows that there is a fundamentally unquestioned hierarchy that has to be broken down at a root level, before one can talk about the limits of competition. All businesses have excuses for cutting wages, unfairly treating employees, etc. Monopolies must only have bigger excuses, because they do it more and worse.

Furthermore, his assertion, "Since [Google] doesn't have to worry about competing with anyone, it has wider latitude to care about its workers, its products, and its impact on the wider world,” is not correct. An appropriate analogy would be between a giant and a regular person. One cannot scale a regular company to be a pure monopoly without sacrificing the benefits of competition; it is the difference between a giant and a normal-sized person. A company is essentially a zero-sum game of resources (minus profit) and staff, and a smaller business has less resources but also less staff. But the small business has something the monopoly does not: competition. Small companies want low turnover to avoid losing employees to competitors, but monopolies fire hundreds of workers (blue collar or white collar) overnight. In other words, competition rather than money plays the biggest role in the treatment of workers. Case in point, Amazon's online shopping and delivery platform pays minimum wage to its workers, shuts down strikes and ignores COVID-19 safety protocols, yet the small companies that sell on their platform perform their competition while maintaining a profit, a good image, and good employee satisfaction.

In a later paragraph, Thiel states, "The dynamism of new monopolies itself explains why old monopolies don’t strangle innovation." Again, there is a problem with the black and white viewpoint on monopolies. A closed system where one company dominates until another innovation arises actually slows down innovation because the incentive to innovate is held by the lucky few.

The last point of contention I have is the statement, "In perfect competition, a business is so focused on today’s margins that it can’t possibly plan for a long-term future. Only one thing can allow a business to transcend the daily brute struggle for survival: monopoly profits." When one says that only monopolies can afford to think into the future and cause progress, they are mischaracterizing the nature of business. All businesses that compete in their markets have no choice but to afford to create technological change on a gradual level regardless of the level of their finances. Why this is important is that a larger quantity of smaller increments in progress will always outproduce a big jump before a long stagnation. Monopolies will stagnate in their growing wealth having no necessity to act until there is a big opportunity to make more, while competition by other businesses will drive relentless progress. “Creative monopolies” as defined in chapter 3, are really just a myth. There are only regular monopolies: the ones that dominate an industry causing technological stagnation, and the next monopoly after that does too. Like people retire well by saving money slowly, businesses in competitive markets improve technology through small processes rather than large ones.

A lingering problem that stays on my mind after reading chapter 3 is the perspective on monopolies that Thiel gives. Like an economics book, many times his writing seems to show a side of things that people don’t normally think about. Thiel gives a reasonable motivation for monopolies in order to shake up those who don’t normally think about the opposite perspective. Additionally, he adds fuel to his foundational beliefs on technology vs. globalization. But to me it is an egregious error when he states, among other things, “To an economist, every monopoly looks the same, whether it deviously eliminates rivals, secures a license from the state, or innovates its way to the top. In this book, we’re not interested in illegal bullies or government favorites: by 'monopoly,' we mean the kind of company that’s so good at what it does that no other firm can offer a close substitute. Google is a good example of a company that went from 0 to 1: it hasn’t competed in search since the early 2000s when it definitively distanced itself from Microsoft and Yahoo!”, and then he goes on to say in a later paragraph, "Monopoly is therefore not a pathology or an exception. Monopoly is the condition of every successful business."

By Oxford Dictionary’s definition, a monopoly is “the exclusive possession or control of the supply of or trade in a commodity or service.” So when a monopoly advances to the forefront of their trade, they forego competition by default. All a monopoly is is a large business, and like a government, it is simply one large entity that has self-driven desires. It is not “so good at what it does”, the market is a zero-sum game where the monopoly pushes other companies down to rise above their dust. One cannot expect a company that's at the top to do something that doesn't profit itself, even it if means sacrificing innovation.

Moreover, the condition that Thiel purports, "perfect competition", where all businesses are at equilibrium and profit is nullified by competition, is hardly the case in America's economy. Instead, competition has always been the equalizing factor, the factor that brings about change and innovation. Individual companies’ benefits collide and compete in the market, which brings innovation to consumers and benefits to the nation. The global economy, sans competition, has had “creative monopolies” drive it forward? That’s just plain wrong. Even in America, Microsoft, FAANG, and other big companies have raked a lot of profit, but 50% of the GDP is still those 27 million small businesses. In other countries, small businesses are a whole lot more of the GDP.

Of course, the backbone of a nation is people, while for companies it is profit. So, one shouldn’t assume that progress will flow freely from the monopolization of profit. Those companies will have the ability to improve technology but only will do so as long as it profits them. This reasoning applies no matter how “evil” or "good" the company in question is.

Comments